Private sea rescue in the Mediterranean

Infografik Nr. 708073

Verlinkung_zur_deutschen_Ausgabe

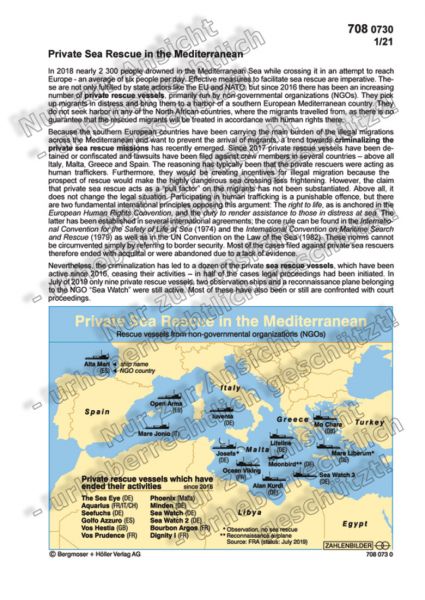

In 2018 nearly 2 300 people drowned in the Mediterranean Sea while crossing it in an attempt to reach Europe - an average of six people per day. Effective measures to facilitate sea rescue are imperative. These are not only fulfilled by state actors like the EU and NATO, but since 2016 there has been an increasing number of private rescue vessels, primarily run by non-governmental organizations (NGOs). They pick up migrants in distress and bring them to a harbor of a southern European Mediterranean country. They do not seek harbor in any of the North African countries, where the migrants travelled from, as there is no guarantee that the rescued migrants will be treated in accordance with human rights there.

Because the southern European countries have been carrying the main burden of the illegal migrations across the Mediterranean and want to prevent the arrival of migrants, a trend towards criminalizing the private sea rescue missions has recently emerged. Since 2017 private rescue vessels have been detained or confiscated and lawsuits have been filed against crew members in several countries – above all Italy, Malta, Greece and Spain. The reasoning has typically been that the private rescuers were acting as human traffickers. Furthermore, they would be creating incentives for illegal migration because the prospect of rescue would make the highly dangerous sea crossing less frightening. However, the claim that private sea rescue acts as a “pull factor” on the migrants has not been substantiated. Above all, it does not change the legal situation. Participating in human trafficking is a punishable offence, but there are two fundamental international principles opposing this argument: The right to life, as is anchored in the European Human Rights Convention, and the duty to render assistance to those in distress at sea. The latter has been established in several international agreements; the core rule can be found in the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (1974) and the International Convention on Maritime Search and Rescue (1979) as well as in the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (1982). These norms cannot be circumvented simply by referring to border security. Most of the cases filed against private sea rescuers therefore ended with acquittal or were abandoned due to a lack of evidence.

Nevertheless, the criminalization has led to a dozen of the private sea rescue vessels, which have been active since 2016, ceasing their activities – in half of the cases legal proceedings had been initiated. In July of 2019 only nine private rescue vessels, two observation ships and a reconnaissance plane belonging to the NGO “Sea Watch” were still active. Most of these have also been or still are confronted with court proceedings.

| Ausgabe: | 03/2021 |

| Reihe: | 53 |

| color: | Komplette Online-Ausgabe als PDF-Datei. |

| Reihentitel: | Zahlenbilder |

| s/w-Version: | Komplette Online-Ausgabe als PDF-Datei. |